Why You Shouldn't Support Mandatory Vaccinations

last updated 9/03/2021

Need help deciding how you're going to power your beer fridge? This is a design guide for 12V systems or dual battery systems used in vehicle setups for touring and camping. It is not a guide on how to actually wire up equipment, terminate cables, use a soldering iron etc. It is not recommending which setups are good or bad. The purpose is to explain different solutions to this design problem (good and bad) and identify what equipment would suit your application and how to arrange them in your design. The drawings are not wiring diagrams, they are schematics showing topology only. All wiring should be done according to equipment datasheets and manuals. All designs should be checked and installed by a qualified auto-electrician.

Every design is a compromise. This guide gives you the info you need to pick your compromise.

Dual Battery Systems

A dual battery system is where one or more auxiliary batteries are installed in addition to the standard starter battery of a car, 4WD or motorhome. The arrangement provides additional battery capacity to allow appliances like fridges and lighting to be powered, and prevents these appliances from loading the starter battery, ensuring your engine will start even after lengthy use of the appliances. Dual battery systems are common in touring vehicles set up for camping, fishing and travelling around the outback.

One or More Batteries

Whether there are one or more auxiliary batteries, and whether they are installed in the vehicle, under the bonnet, in the passenger cabin, in the tray, in a trailer or in a caravan, does not effect the design arrangements outlined in this article. For the purpose of simplicity, this article will refer to only one auxiliary battery. A bank of batteries in parallel behaves the same as one large battery. Wherever you see "second battery" or "auxiliary battery" you can replace it with a bank of batteries. Batteries arranged in banks work best if they are matched, so that they have matched voltage profiles and charge / discharge at the same rates, but this is not absolutely necessary. All lead acid batteries behave fairly similarly. When connected in parallel, batteries do not need to be exactly matched, as charge and discharge current will naturally distribute between them according to their capacity. A larger battery or a battery with less internal resistance will sink more current when charging as it pulls down the charging voltage. That battery will supply more current under discharge as its voltage will not drop as much.

Types of Batteries

An auxiliary battery is most likely going to be cycled. That is, discharged at slow to moderate currents for long periods of time and then recharged. This is different to a starting battery, which needs to deliver high currents for short periods, but does not get depleted or cycled significantly. Cycling lead acid batteries wears them out, causing sulfation of the negative electrodes. Deeper discharges cause a disproportionate increase in wear. Double the discharge depth, and the damage to the battery is more than doubled.

Batteries used for cycling applications are specially designed to minimize wear caused by deep discharges, at the expense of reduced high current ability, increased weight and increased cost. They are called deep cycle batteries and are the type of batteries that should be used as the second battery in dual battery systems.

Putting your deep cycle battery in parallel with your starter battery is not a perfect arrangement, as they are of two different battery types. However the charging profiles and voltages of standard flooded batteries vs deep cycle batteries are very similar, practically identical for most batteries. So it can almost always be done without any issues. Check the datasheets for any significant difference between specified float charge and cycle charge voltages. Most batteries are 13.8V float and 14.5V cycle, or pretty close to those values.

A particular design of deep cycle batteries, called Absorbent Glass Mat (AGM) batteries, are especially suited to dual battery systems and should be considered in any design. The advantages of AGM batteries over standard deep cycle batteries include:

- Much higher charge rate (up to 5 times higher). This gives you the ability to perform quick top up charges from the alternator by running your vehicle. A half hour charge from the alternator could add say 25Ah, compared to only 5Ah with a standard deep cycle battery.

- Higher specific power (can provide higher short term current, useful if you have a problem with your starting battery)

- Greater tolerance to vibration due to glass mat sandwich construction

- Spill-proof

Disadvantages of AGM batteries are:

- More expensive

- Fewer number of charge / discharge cycles compared to standard deep cycle batteries

- Lower specific energy (heavier battery)

- Capacity has gradual decline as the battery wears. Standard deep cycle lead acid batteries have a flatter decline to start with, maintaining a greater proportion of original capacity for longer, before losing capacity quickly towards the end of its life.

Batteries degrade with elevated temperatures. Higher temperatures reduce battery life. Try to install your battery in a cool location, away from hot parts of the motor or out of the engine bay completely. Sealed batteries are a good choice, as they can be stored inside a vehicle without the risk of spillage or dangerous gas venting. As a guide, every 8 degrees Celsius rise in temperature halves the life of a typical lead acid battery. That's pretty significant when considering how hot it gets under the bonnet of a car with the engine running, especially in the sun on a hot day.

For more information on battery chemistry, visit http://batteryuniversity.com

Electrical Protection – Fuses and Circuit Breakers

Fuses and circuit breakers protect cables and equipment from electrical faults. They work in the same manner – interrupting the path of electrical current during fault conditions. They are available in a range of current ratings to suit various applications. They should be rated such that they will not trigger during any normal loading (including inrush from starting appliances), but need to be rated as small as possible to ensure they are activated in a timely manner during a fault. The biggest risk in a 12V system in the event of an electrical fault is fire. A fault can occur during a car accident, equipment failure (short circuit in an appliance), cable insulation deterioration, etc. Fuses and circuit breakers should be used to reduce the risk of fire and minimize damage in these circumstances.

Fuses have a wire element that melts due to the heat generated from high current, creating an open circuit in the event of a fault. The advantages of fuses over circuit breakers are lower cost and faster acting (minimizes damage).

Circuit breakers work through thermal and / or magnetic pickups that are triggered by high current. Circuit breakers are resettable whereas fuses need to be replaced once they have blown.

To avoid cluttering drawings and repetition, fuses and circuit breakers will not be covered in each section. Instead apply general principles to your design:

- Fuses and circuit breakers should be used in any 12V system. Omitting fuses could lead to fire and denial of insurance claim. Ideally every cable feed should be individually protected, but this introduces complexity. The design is a trade-off between complexity and fault discrimination.

- Place fuses and circuit breakers on the positive side of cable runs

- Fuses and circuit breakers should be placed as close to the battery as possible to minimize the unprotected portion of the cable run between the battery and fuse / circuit breaker.

- The highest risk occurs where there are bigger cables, as these cables will carry a higher fault current. For example the cables that link the starting battery with the auxiliary battery, or the cables that feed an inverter.

- A cable linking two energy sources needs to be protected from both ends. So the cable linking the positive terminals of the starting battery to the auxiliary battery should have a fuse or circuit breaker at both ends.

- If you are distributing power to many different locations via many cables, it may be impractical to individually fuse each run. In this case you can use one common fuse or circuit breaker for the main feed, then distribute to the other cables after that point.

- Protecting every cable run individually provides discrimination between faults. When a fault occurs, only the fuse feeding that run will blow, automatically pointing you to the location of the fault and leaving your other cable feeds energized.

Earthing of an Auxiliary Battery

The negative terminal of the auxiliary battery can either be connected to a metallic part of the vehicle, or connected directly back to the starter battery via a dedicated cable. Both ways work. Running a dedicated cable ensures you will get a low resistance connection, but is more expensive and could be considered wasteful. Earthing to the nearest metallic part of the vehicle reduces the length of heavy and expensive cable used in the design, but could introduce problems from high resistance joins in the chassis, engine etc, for example where two sections of chassis are bolted together, or between the chassis and the engine. You may need to add short cable links across any high resistance joins. It can be difficult to prove whether the resistance through the chassis is acceptable. The least risk option is to run a dedicated cable back to the starter battery.

I don't have a dedicated negative return cable. I connected my aux battery to the chassis and tried to crank the engine from it with the starter battery disconnected. Cranking the engine is a good test for resistance and voltage drop. On the first test the engine could not start. I added a short cable link from the chassis to the engine and the engine started successfully.

Sizing Your Auxiliary Battery

Battery sizing is determined by the load and how long the loads need to run without charging. Calculate the amp hours (Ah) consumed over that period, double it, and that gives you the Ah capacity of the battery required to meet that criteria. Doubling is so that you deplete the battery to 50% and no lower. The deeper you discharge a lead acid battery, the greater the damage you cause, and the damage grows disproportionately with depth of discharge. Around 50% is a good compromise. If you want the batteries to last longer you'd size them so they will discharge to say 75% of full capacity before being recharged. The tradeoff is the expense of needing more batteries and the extra space / weight.

As an example, let's assume our loads are a fridge that consumes an average of 2A, and an incandescent light rated at 240VAC 60W that you want to run for 2 hours a day. Let's say you would like the system to run for a whole day – 24 hours.

To convert the AC power of the light to DC current, divide power by 12 and multiply by 1.1 to take into account the energy wasted converting from AC to DC. Multiply the currents by the run times and add them together.

Fridge Ah: 2 x 24 = 48Ah

Light Ah: 60 / 12 x 1.1 x 2 = 11Ah

Total Ah = 48 + 11 = 59Ah

Battery capacity = 59 x 2 = 118Ah

That's a good sized battery. What if you run your alternator for 30 mins / day? This might be to drive down to the fishing spot and back to camp or might be idling the engine specifically to charge the battery. The charge rate is difficult to predict. Let's assume you have an AGM battery that can accept a pretty good charge rate and take a guess of 30A. That's 15Ah if it runs for 30 mins. The calculations change as follows:

Total Ah = 48 + 11 – 15 = 44Ah

Battery Capacity = 44 x 2 = 88Ah

What if you have solar panels that are large enough to fully charge the batteries every day? Then the batteries need to last say 16 hours between charges. The lights run at night so the full 2 hours are still used during the discharge phase.

Fridge Ah: 2 x 16 = 32Ah

Light Ah: 60 / 12 x 1.1 x 2 = 11Ah

Total Ah = 32 + 11 = 43Ah

Battery capacity = 43 x 2 = 86Ah

The Simplest System – Direct Connection of a Second Battery

A second battery can be connected in parallel with the starter battery with no other additional hardware as shown in the circuit diagram below.

This system is simple to install and minimizes costs. The alternator will charge both batteries and all loads will be shared between both batteries. Both batteries will contribute to cranking the starter and both batteries will provide capacity to run the auxiliary loads. The main problem with this arrangement is that the starter battery will be depleted by the auxiliary loads, after which the vehicle will be unable to start. An easy solution is to manually disconnect the starter battery as required. This is the arrangement I used in my early years of camping. The starter battery in my vehicle had round terminals that were tapered in shape. This meant I could leave the nuts on one of the terminals slightly loose, and with some shuffling back and forth of the terminal I could wedge it hard enough onto the tapered battery terminal to provide a good enough connection, or I could disconnect the terminal as required without needing any tools. You run the risk of forgetting to disconnect the starter battery and allowing it to go flat. If you use this setup, ensure you disconnect the negative terminal only to prevent accidental short circuiting of the auxiliary battery on the body of the vehicle, and obviously do not allow the loose negative terminal to touch the positive side of the battery, unless you are trying to start a fire.

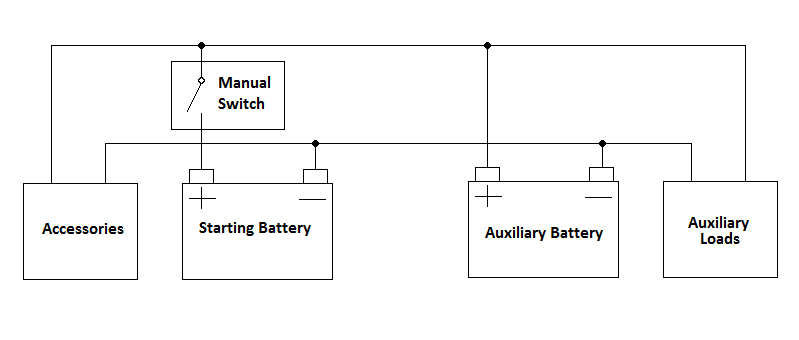

Manual Isolator Switch

Rather than playing around with battery terminals every time you disconnect and reconnect, a switch can be added in circuit. The switch can be a basic isolator switch or a relay that is toggled in and out via another switch, usually positioned inside the vehicle cabin. It could also be a connector or anderson plug which you manually disconnect. This system still relies on manual intervention to ensure the starter battery is not depleted.

The switch can be placed in one of two locations. The first location keeps the starting battery powering the vehicle accessories such as interior light, stereo, etc. This has the advantage of not interfering with the vehicle's standard electrical distribution so that it is easy to revert back to factory arrangement, and allows the starter battery to contribute to some of your power requirements so that your auxiliary battery is not cycled as deeply. This results in a net reduction in battery wear across the two batteries and some extra usable battery capacity. It also keeps the starting battery in circuit ready to start your vehicle regardless of the position and condition of the switch (for example if the switch fails). It also places less stress on the switch, as starter motor current does not flow through it. The problem with this arrangement is that it allows your starter battery to become depleted from the vehicle's accessories.

The second location for the switch shown below completely isolates the starting battery so that there is completely no load on it. The battery will stay charged indefinitely (apart from self discharge), but the battery will not contribute to your power use, the switch will be under greater stress during starting and the failure of the switch may make your vehicle unable to start. Instead of a manual switch or relay, the relay can be driven automatically from your accessories being turned on. So when you turn the keys to accessories the relay is energized and closes the circuit. This removes any manual intervention, but adds the complexity of wiring from an accessories power feed to the relay. It can be placed in either location in the two schematics above with the same pros and cons as using a manual switch, relay or connector.

Instead of a manual switch or relay, the relay can be driven automatically from your accessories being turned on. So when you turn the keys to accessories the relay is energized and closes the circuit. This removes any manual intervention, but adds the complexity of wiring from an accessories power feed to the relay. It can be placed in either location in the two schematics above with the same pros and cons as using a manual switch, relay or connector.

With either the manual switch or accessory driven relay, your auxiliary battery will contribute to starting your engine, which is useful if your starter battery is tired.

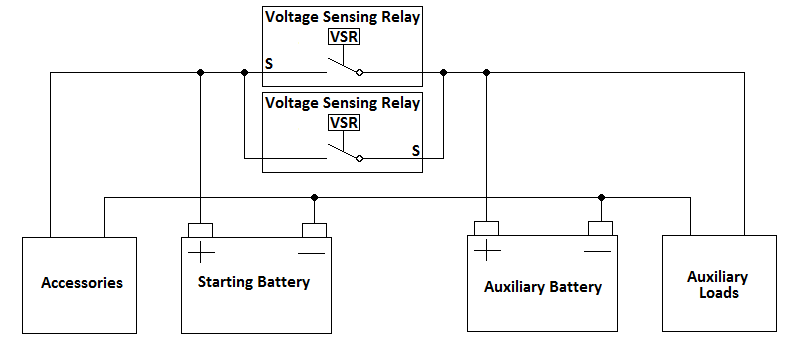

Voltage Sensing Relay

A voltage sensing relay is the most common dual battery arrangement. Most dual battery isolators are of this type. The voltage sensing relay isolates the starter battery when the starter battery's voltage goes below a setpoint level. This allows the starter battery to contribute to your power requirements to a small extent, up to the point where it is isolated. It is fully automatic, does not require any manual intervention and does not require any control wiring from accessory feeds or other switches so is easy to install. When your motor is started, the alternator will charge the starting battery and raise its voltage. The voltage sensing relay will close once the voltage exceeds a setpoint level, joining the two batteries together and allowing your auxiliary battery to be charged from the alternator. The "S" indicates the sensing terminal on the voltage sensing relay.

The voltage sensing relay must be in the location identified in the schematic, otherwise once it opens you would never be able to start your engine. Your starting battery is still at risk of being depleted by the vehicle's accessories. It also does not permit the auxiliary battery to contribute to engine starting once the starter battery's voltage is below the switching setpoint voltage. This will prevent you from otherwise being able to start the engine if the starter battery is flat but the auxiliary battery is fully charged. Some voltage sensing relays can be forced to close, for example through a switch or connecting a link or jumper. This allows your auxiliary battery to contribute to starting the motor.

Dual Voltage Sensing Relays

If you have some sort of charging system for your auxiliary battery (eg solar panels), the single voltage sensing relay has a drawback. Once it opens, it prevents your charging system from charging your starter battery, and your starter battery will be slowly depleted by your vehicle's accessories. Adding a second voltage sensing relay in the reverse direction resolves this issue. The batteries will be joined if the voltage on either side is high enough. So once your charging system has charged your auxiliary battery, the second voltage sensing relay will close and your starter battery will be charged. Apart from avoiding depletion of your starter battery, this arrangement allows your starter battery to contribute to your power use every charge / discharge cycle, so you have some extra capacity to run your loads longer, and it allows the auxiliary battery to contribute to starter motor cranking. It also reduces the depth of discharge on your auxiliary battery, resulting in a net reduction in battery wear across the two batteries. It, if the charging system on the auxiliary side permits, also gives your starting battery an occasional higher charge voltage above the standard voltage of the alternator, which reduces sulfation and extends battery life. There are dual voltage sensing relays available that perform this function as a single unit – closing when either terminal is a high enough voltage. So the system can be arranged with either two standard voltage sensing relays or one dual voltage sensing relay.

The charging system (solar panels) is not included in the schematic. They are treated separately in the solar panels section.

DC-DC Converter

Charging your auxiliary battery with your vehicle's alternator is good but not great. It does not provide a boosted voltage output after a battery cycle down. This means, in cycling applications, the battery will suffer from sulfation which will accumulate with each cycle and eventually cause premature battery failure. Further, the alternator's limited output voltage means charge rate becomes very slow as the battery approaches 100% state of charge. Also it does not provide an adjustable output to suit a battery with unusual float and cycle voltage ratings. A solution is to use a DC-DC converter. This is an electronic multi-stage charger that is powered by your alternator. During certain times of the charge cycle it ramps the voltage up to around 14.5V. This charges your battery faster in the final stages which may offer a higher state of charge. The higher voltage also reduces sulfation which reduces the damage caused by each cycle down and extends battery life. A further advantage is that it separates the charging between your starter and auxiliary batteries, so you can use an auxiliary battery with unusual float and cycle voltages, provided the DC-DC converter can be configured to charge at those voltages. Another advantage is that the cranked up voltage can help offset some volt drop if you have a long cable run (for example to a trailer) and are not able to keep volt drop within acceptable limits.

DC-DC converters are good but they are not perfect. They have the following disadvantages over traditional voltage sensing relays:

- Reduced charge rate during bulk charge: DC-DC converters are usually rated to around 20A or so. If your battery is able to accept more current, the DC-DC converter will not be able to provide it. Alternators can typically charge up to around 100A, which is especially useful if you have an AGM battery which is capable of being charged at very high charge rates (30 to 40A for typical AGM batteries or more for very large batteries). When there's other loads connected to your auxiliary battery, such as fridge etc, this further reduces the charge rate from a DC-DC converter as some of the current is diverted to the loads whereas the alternator will be able to supply those loads whilst still supplying as much current as the battery will take.

- Overcharge: DC-DC converters always charge at elevated voltage on startup even when the battery is already fully charged. It takes a short period of time for the charger to recognise that the battery is fully charged and revert to float voltage. This may cause a small amount of unnecessary overcharge and the associated grid corrosion. When not cycling the battery, the voltage should remain at the float voltage at all times (usually around 13.8V). The alternator voltage is chosen for a reason – it is an appropriate float charge voltage for most batteries. Startup overcharge is minor. More serious is overcharge caused by loads triggering the DC-DC converter to go to cycle voltage when the battery is already fully charged. See section below "Overcharge from DC-DC Converters and Solar Regulators."

- Inability to supply large loads: if you have a big compressor that uses 50A or a power hungry appliance hanging off an inverter then your auxiliary battery will become depleted even with the engine running because the DC-DC converter can't keep up with the load. This could be a problem if the high load is sustained, for example if you have the only good compressor and need to pump up all your mates' tyres, or you have a high maintenance wife who needs to use the hair dryer on camping missions.

- Does not allow a charging system on your auxiliary battery to charge your starter battery: You can't backfeed from the auxiliary side to the starter side. Some DC-DC chargers, with dedicated solar inputs, will allow solar panels to charge both the starter battery and auxiliary battery.

- Does not allow the auxiliary battery to contribute to cranking: You can't use the auxiliary to crank your engine if the starter battery is flat or if it's failed completely. This is a problem if you're out bush. I did have my starter battery fail whilst travelling around Australia and was able to use the auxiliary to start my hilux since I use VSRs.

- Too slow when charging battery banks: if you have a bunch of batteries in parallel sharing the charge from a DC-DC converter then you're going to be waiting a long time to charge the batteries. Also, since the batteries may not charge identically, there's increased chance of overcharging the batteries since those that are charged quickly will be held at the cycle voltage for too long. Usually batteries of similar age and type do charge at about the same rate since the higher charged battery will naturally sink less current and the flatter batteries will catch up.

DC-DC Converter Myths

I've noticed a lot of misinformation about DC-DC converters so I've added this section to help clear the water. The most commonly reported myth is that your alternator cannot fully charge a battery. Often a figure of 80% is quoted as the maximum charge that an alternator can provide, but I've seen figures as wild as 60% being reported. I have found exactly zero substantiated references to support these claims. I have seen exactly zero adequate explanations to support these claims. It's not true. The figure of 80% sounds like an arbitrary number that some marketing guy made up. Nothing special happens to a battery's chemistry when it reaches 80% state of charge. In reality any voltage above the voltage dictated by the battery's chemistry will charge the battery to 100%. You can verify this by looking at charge characteristic curves on battery datasheets – the capacity approaches 100% for any charge voltage. It is true that the final portion of charging will be slow from an alternator. Perhaps extremely slow depending on the output of your alternator. An elevated voltage will charge the final few % faster and help reduce sulfation.

On average, under cycling conditions, an alternator will provide a greater state of charge. After an overnight discharge, an alternator will charge faster than a DC-DC converter during the bulk charge stage. This accounts for most of the battery's capacity. For a typical AGM battery size of 100Ah , the alternator may charge at say 40A whereas the DC-DC converter will be limited to its rating, typically 20A, or even less at elevated temperatures. With loads like fridges connected, the DC-DC converter will charge the battery even slower as many amps are diverted to the loads, whereas the alternator has excess capacity to supply the loads as well as continue to charge the battery at 40A. So in a typical scenario, driving from camp site A to camp site B, or driving from camp site to fishing spot, or running your motor specifically to top up the batteries, direct charging off the alternator will be charging over twice as fast as a DC-DC converter. That's over 20A more current. Unless driving for a very long time, the battery will never be fully charged in this scenario. It is only once the battery is almost fully charged that a DC-DC converter will charge faster than the alternator. On average though, for a typical cycle of the battery, you'll have more capacity charging from the alternator.

I've seen other myths reported about DC-DC converters. For example that they are "better for your loads", or provide "better isolation", or that they help your starter battery charge to a higher capacity or improve longevity in your starter battery. These are all untrue. Disadvantages of DC-DC converter are numerous as illustrated above.

Some claim that if cost is not an issue, a DC-DC converter is universally the best solution for a dual battery design. Even with infinite budget, I do not believe this to be the case, although DC-DC converters do have advantages that should be considered. Any design is a compromise.

If your auxiliary battery is able to accept a high charge rate from the alternator and will see regular charging from adequate solar and / or an intelligent mains charger then I prefer the advantages of a dual VSR setup.

If you have a fixed voltage alternator and its output is lower than the specified float voltage of your battery then you probably need a DC-DC converter. If you have a smart variable voltage alternator that spends a lot of the time at reduced voltage and won't respond to loads by cranking up the voltage then you probably need a DC-DC converter. Or if you never have a solar or mains system giving regular high voltage top ups to give the battery 100% charge and reduce sulfation then again you should consider a DC-DC converter.

Remember, a DC-DC converter is the most expensive solution for a dual battery system. Therefore it is the preferred solution for anyone selling this stuff. Keep this in mind when assessing marketing information.

DC-DC Converter with Shorting / Bypass Relay

Some of the disadvantages of the DC-DC converter is that it does not allow your auxiliary battery to contribute to starting your motor, will not allow a charging system on your auxiliary battery to charge your starting battery and charges too slowly during the bulk charge phase of a depleted battery. A solution is to add an extra relay that directly connects your batteries, bypassing the DC-DC converter. The relay would be manually activated whenever you need the batteries directly connected. The relay needs two contacts of opposite sense – one to connect the batteries together and one to open the supply to the DC-DC converter. This shuts off the DC-DC converter, preventing damage which could result from shorting the input and output of the DC-DC converter. The DC-DC converter may protect itself from destruction if its input and output are shorted but it's a good practice to disconnect the DC-DC converter when shorting.

So if you have a depleted battery and you're driving a short trip from camp site to fishing spot, you could activate the switch and top up your battery more quickly. Or if your starter battery is struggling to crank your engine you could activate the switch so the auxiliary battery helps.

More Fancy DC-DC Chargers

Some battery system vendors have their own solutions for overcoming some the of limitations of DC-DC chargers. Some may offer their own solution that achieves a similar result to having a bypass relay. Some combine solar charging input with alternator DC input. Some add on top of that a mains AC input. Examples include smart bypass and battery manager. Building a complete system using these most fancy combinations of a dual battery system vendor's products can run into many thousands of dollars. A similar result can be achieved with a dual voltage sensing relay, solar regulator and separate mains charger.

Modern Variable Voltage Alternators (Smart Alternators)

Some modern vehicles have engine management controlled alternators with various modes of operation. The voltage is cranked up to recover energy from a decelerating vehicle. The voltage is also cranked up if it is detected that the battery needs a charge. The voltage is ramped down at other times to save fuel. An intermediate voltage is used when the battery is fully charged but there are constant loads energized such as headlights. The system models the starter battery's state of charge and uses inputs from various loads and / or load current sensing to determine the different modes of operation. This works great with the factory arrangement but if you want a dual battery system the following problems may arise depending on the implementation:

- The system only elevates the voltage during energy recovery mode which is not enough time to charge the aux battery properly.

- The system's model calculates that the starter battery is fully charged and sets itself into fuel saving mode which reduces the voltage output. The aux battery does not get recharged.

- The current flow to the aux battery and / or auxiliary loads triggers the system to permanently elevate its voltage output. If the starter battery or aux battery are fully charged then they suffer from overcharge and diminished life.

Solutions to these problems are:

- Force the system into fixed voltage output mode so it behaves like an old style vehicle. There may be a jumper or relay contact that needs to be shorted to activate this mode. The manufacturer / dealer should be able to do this. This is my preferred solution. Fixed voltage output means predictable results and tolerance to any combination of loads and wiring arrangements.

- If the factory system has load current sensing, then ensure the dual battery system is arranged so that any current flow to the aux battery / aux loads are also measured by the load sensing.

- Use a DC-DC converter. This will crank up the voltage to ensure the aux battery is charged. The starter battery is still at risk of overcharge, depending on how the extra load is interpreted by the system.

- Wire it up like an old school system and see if it works. It may work well depending on how the charging system has been implemented on the particular vehicle.

Charging 12V Systems from AC Mains

There are many 12V battery chargers available. Less sophisticated chargers are simply unregulated power supplies. These are ok, but do not boost the voltage to charge faster and minimize sulfation, and do not terminate the charge once the battery is fully charged, risking overcharge. Ensure you manually disconnect these chargers when the battery is full charged, or after say a maximum of 48 hours when charging a flat battery. Usually these types of chargers have a fairly low voltage output and so will take a while to cause significant overcharge.

Electronically controlled and regulated chargers are the best solution for charging 12V lead acid systems. They offer higher charge rates, optimized charge profiles to extend battery life, and will terminate the charge when the battery is fully charged (backing off to float charge voltage at this point). They offer reconditioning cycles which attempt to dislodge sulfur from electrodes and restore some battery capacity. Using these chargers may extend the life of your batteries.

Some people permanently mount an AC charger in the vehicle or trailer. It is permanently wired to the 12V system so that it's just a matter of plugging it in to begin charging. This is useful if you are visiting powered camping sites regularly, such as those found in caravan parks. Make sure you have a switch to isolate the AC charger on the DC side when not in use, otherwise it may sink some current whilst turned off and flatten your batteries. My CTek intelligent charger draws a few hundred mA when switched off and connected to my battery. Most other chargers will probably be similar.

To get around the fact that, at the start of your trip, a setup with a VSR relay may yield a state of charge less than 100%, you can hook up the mains charger half a day or a day before you leave. This will top up your batteries to maximum capacity whilst still affording all the benefits and simplicity of a VSR system. You can also run your fridge without depleting the batteries so that it's ice cold when you leave.

Charging 12V Systems with Generators

Many generators have a 12V supply which can be used for charging 12V batteries. Usually the current capacity is quite low – around 8 amps. So charging from a generator using its 12V output will be slow. It's also wasteful, under loading the generator and thus wasting fuel. The generator is almost idling and you need to let it run for hours. Another problem with the generator 12V output is it is not regulated nor does it terminate the charge when the battery is full. If the output voltage of the generator under no load is around 13.8V or below then it's fairly safe to leave it connected to the battery for long periods. A higher voltage will eventually overcharge the battery and reduce battery life.

A better solution is to purchase a regulated mains AC charger. Don't use the generator's 12V supply. Get a regulated charger and plug it into the generator's AC source. The benefits include faster charging and less fuel wasted. Also, with the right type of electronic charger, the charge will automatically terminate when the battery is full, preventing over charge.

There are dedicated 12V petrol chargers available. The design typically has an engine turning a vehicle alternator. Capable of delivering up to 100A, they are the fastest and most fuel efficient way to charge a 12V battery by generator. However they will not terminate the charge when the battery is full and lack the flexibility of a generator that can power your 240V appliances as well. It might not be practical to invest in such a specialised generator.

Charging 12V Systems with Alternator Booster Diodes

A booster diode is connected to the alternator's regulator to trick the alternator into increasing its output voltage. As a battery becomes full this will help charge the battery faster. A voltage increase of 0.5V is typical.

A vehicle's alternator has no regard for the state of charge of the batteries. It will keep trying to charge indefinitely. For this type of charging arrangement, the voltage should not exceed about 13.8V or as defined under "float charge" on the battery's datasheet. This voltage is the best compromise between charge rate and minimizing overcharge, grid corrosion and elevated temperatures. This is why car alternators regulate to around 13.8V and why most battery datasheets indicate 13.8V as the float charge level. Alternator booster diodes will permanently elevate the voltage, leading to increased grid corrosion, higher battery temperatures, increased risk of venting and reduced battery life. If your alternator voltage is below 13.8V and a booster diode brings it to 13.8V then that is ok. Boosting to higher than 13.8V and holding it permanently at the elevated voltage will reduce battery life.

For more information on battery charging, visit http://batteryuniversity.com

Solar Panels

Solar Panels can be used for charging your batteries. They provide a good solution for those that want to be self sufficient and go on long camping missions through remote areas. They are available in various voltage and power ratings. More than one solar panel can be used in parallel to combine their power output. Solar panels joined in parallel work most efficiently if they are the same. If they are the same, you can design it so that they both generate power at their optimal operating points. Mixing different panels together gives a compromised operating point. It will work but the panels will not operate as efficiently.

Solar Panel Poly or Mono

Silicon solar panels have two basic construction methods – polycrystalline or monocrystalline. There are slight differences between poly and mono cells. Mono are slightly more expensive, require more energy to make, and are slightly more efficient. Poly are slightly cheaper, use less energy to make so are better for the environment, are slightly less efficient but have a slightly better temperature coefficient. That means at elevated temperatures the poly cells become more efficient.

The differences are only slight. It's largely irrelevant. Find a solar panel with good efficiency and good temperature coefficient and at the right price. Whether it's poly or mono does not matter.

Solar Panel Sizing

How much solar panel do you need? You can get a rough idea from the loads you want to run. It's best to work in power when calculating solar panel load. It avoids confusion when running appliances at different voltages (for example AC appliances through an inverter). The current provided by a solar panel is also difficult to calculate due to the complexity of their optimized voltage vs current relationship. So work in watts (abbreviated to W) and watt-hours (Wh).

Calculate your load

Determine the power use of each appliance and how long they will be operated for. Check appliance datasheets or nameplates. If their consumption is in amps, multiply by their voltage to yield their power. If they are AC loads driven by an inverter, multiply the power by 1.1 to take into account the losses in the inverter.

You want to calculate the total Wh consumed in a 24hr period. Multiply the power consumption of the appliance by the number of hours it runs per day and sum together with all the other appliances.

As an example – a large fridge that is rated at an average of 2.1A at 12V, a small fridge used as a freezer rated at 1A at 12V (double the rated current use when used as a freezer – 2A instead of 1A), an LED light rated at 0.5A at 12V that operates for a couple of hours per day, and an 240V AC television rated at 180W used for a couple of hours per day.

Large fridge Wh: 2.1 x 12 x 24 = 605Wh

Freezer Wh: 2 x 12 x 24 = 576Wh

LED Light Wh: 0.5 x 12 x 2 = 12Wh

TV Wh: 180 x 1.1 x 2 = 396Wh

Total energy consumption over 24hr period: 605 + 576 + 12 + 396 = 1589Wh

Calculate the Size of Solar Panels to Supply the Load

The size of solar panels you need is the energy consumption in a 24hr period divided by the number of hours in a day that the solar panels produce energy for. For number of hours, we use peak sun hours (see explanation below). If we assume we are travelling in sunny areas with 7 peak sun hours per day we get:

Solar Panel Rating = 1589 / 7 = 227W

So in this case you need around 227W of solar panels. Or do you? What if it's cloudy? What if your panels are dirty? What if your panels are not faced directly at the sun and at the correct angle? What if you leave the lights on longer than calculated? What about the loss in panel efficiency with elevated temperatures? What about loss in panel efficiency as they age? What about the fact that your solar regulator is not 100% efficient? What about the charging efficiency of the battery? What about the variation in load from the fridge depending on ambient temperature? What about variations in irradiation due to season? What about variations in irradiation from different locations as you travel around? What if, at the same time, you want to chill a carton of warm beer, charge your laptop, charge your torch and crank some tunes on your stereo?

So the equation would become incredibly complicated if you were to try to work it all out. You need to multiply by a fudge factor. The fudge factor is a number anywhere between 1 and infinity. It's simply down to probability of running out of power. The fudge factor should be at minimum 1.2 to overcome just the efficiency losses in charging. Assuming you run your system 24 hours a day 365 days a year, if your fudge factor is 1, then you'll run out of power most of the time, since the system is not 100% efficient. If it's 1.2 you might run out of power 100 days a year. If it's 1.5 you might run out of power 20 days a year. There is no way to guarantee power, you are simply shifting the probability. If you are powering life critical systems your fudge factor might be 10 or more. A typical fudge factor might be say 1.3. So in our example it changes:

Solar Panel Rating = 1589 / 7 x 1.3 = 295W

For touring with vehicles, a good sized solar panel is around 100W to 130W. It's a compromise between economies of scale and how awkward and difficult to access / install / maintain / vulnerability to vibrations and movement. Larger panels get pretty heavy and 130W is towards the upper end of what sized panels I would take on a touring vehicle, but you can go as big as you want depending on personal preference and practicalities of your install. Assuming 100W panels, we need:

Number of solar panels = 295 / 100 = 2.95

So you'd need 3 x 100W panels.

Peak Sun Hours

Peak sun hours is a way to standardize how much sunlight a particular area receives at a particular time of year. It's the equivalent number of hours per day when solar irradiation averages 1000 watts per square meter. The units are kWh per square meter per day. I used 7 hours in the calculation above. Peak sun hours for many places in Australia during summer is around 7 hours. Some places it's more, some places it's less. Seven is a reasonable estimate for Australia in summer. What about winter? In southern capital cities on the mainland you might expect 2 to 3 peak sun hours during winter. In Hobart in winter you could be around 1.5 peak sun hours per day. So you can see there is a lot of variation depending on location and season. This has to be taken into account when sizing your panels. If the above system needed to work in Hobart in the middle of winter then, using the same 1.3 fudge factor, the calculation would be:

1589 / 1.5 * 1.3 = 1377 W

So you would need around 14 x 100W panels.

Locations in northern Australia experience little variation in peak sun hours over the changing seasons. It's always around 6. In summer (wet season) the temperatures in northern Australia are high and stay high overnight. The daytime maximum might be for example 40 degrees and the night time minimum 29 degrees. It might stay above 32 degrees for 18 hours a day. This is a huge heat load on your fridge. Add this to the fact that the extreme heat is causing you to drink a carton of XXXX Gold every day and with only 6 peak sun hours to charge your battery, you have a situation where many systems will not cope. To handle this situation you'd use peak sun hours of 6 and a fudge factor of maybe 2.

Solar Panel Positioning

You want your solar panels pointed directly to the sun, perpendicular to the sun's rays. If you have multiple panels then some suggest they should all be positioned the same. Actually each panel individually should be positioned as close as perfectly perpendicular to the sun's rays as possible regardless of the position of the other panels. The voltage vs current relationship and the resistance in the electrical distribution will allow the better positioned solar panels to provide more energy even if it's not as much as when all panels are ideally positioned. Of course the maximum energy is obtained when all panels are ideally positioned in which case they will all be positioned the same.

If your panels are fixed to your vehicle / trailer etc and you're parking up for a day or more then you want your panels to be facing north if you're in the southern hemisphere. Unless it's summer and you're in the tropics above the tropic of capricorn in which case you may actually need to face south! If you're just parking for a short period of time then face wherever the sun currently is or maybe slightly to the west to allow for a couple of hours of movement.

Connecting Your Solar Panels – Direct Connection

You can connect your solar panels directly to your auxiliary battery. This is the simplest system but it's quite a poor arrangement. There is potential to overcharge and damage your battery. A solar panel will continue to charge to its open circuit voltage, which is usually around 17V for panels used in 12V systems. This is much too high for lead acid batteries and will cause excessive grid corrosion and pressure venting and rapid failure of the battery. Small panels will still lead to the overcharge condition, it will just take longer. Another negative aspect to this arrangement is that the solar panel is not allowed to operate at its optimal voltage. The voltage is clamped to whatever the battery voltage is. So your solar panel will not be able to achieve its rated power output and it will take longer to charge your battery.

Solar Regulators

To overcome the limitations of a direct solar panel connection to your auxiliary battery, a solar regulator is used. Some solar panels come with an integrated solar regulator. Some dual battery isolators and DC-DC converter vendors also provide solutions for solar charging and distribution. For the purpose of this article I assume a separate third party solar regulator. Solar regulators charge your battery according to an optimized charging profile, reducing sulfation and grid corrosion and will terminate the charge at the correct voltage. The best solar regulators are of the type Maximum Power Point Tracking (MPPT). These regulators load the solar panels according to their optimized current and voltage characteristics for the given level of irradiation. This ensures your solar panels are operating as efficiently as possible, providing you with the most energy and highest charge rate possible. MPPT solar regulators are the best solution for connecting solar panels. To size your solar regulator, sum the total power output of all your panels together and divide by 12 to give you a current rating. The solar regulator needs to exceed this value. So if you had 2 x 80W panels, the current would be 2 x 80 / 12 = 13.3A. The rating of the solar regulator needs to exceed this.

Some solar regulators have a "load" connection. I have not shown this connection in the diagram above. This is explained in the next section.

If your solar panels will be permanently in the sun then you may want to consider a way to disconnect the solar panels when the engine is running. Otherwise it will be feeding in parallel with your alternator which might not be a problem but could cause damage (unlikely – the solar regulator should drop back to float voltage when the alternator is feeding power) or it could cause an engine check light. You could achieve this disconnection with a normally closed relay opened when the vehicle's keys are in the run position. If your panels are covered when not in use or folded up and put away then you do not need to worry about this potential issue.

Overcharge from DC-DC Converters and Solar Regulators

DC-DC converters and solar regulators crank up the voltage to around 14.5V to charge your battery faster. This elevated voltage is acceptable during recharge and is indicated on battery datasheets as cycle voltage. Chargers sense the current flow and once the current flow reduces below a certain setpoint this is interpreted as the battery being fully charged and the voltage is reduced back to float level (about 13.8V). If you have a load that regularly draws current (like a fridge) then the DC-DC converter or solar regulator will interpret this as the battery requiring a charge and will crank up the voltage accordingly. The charge voltage will be cranked up whenever the load is running even if the battery is already fully charged. This is a problem. The fully charged battery will be experiencing overcharge. Grid corrosion will increase, temperature will increase and pressure will increase. Venting could occur and battery life will decrease.

This is a serious problem for designs utilising DC-DC converters. Since the DC-DC converter is running all the time whenever the engine is running there's a high chance that the battery will experience overcharge conditions regularly. The problem is less for solar regulators since this will impact the battery only when the solar panels are deployed and typically after an overnight cycle down where the battery is in a discharged condition.

A solution for those running DC-DC converters is to separate the loads via some additional relays and circuitry. Some DC-DC converter vendors may offer their own solution. This problem can be avoided completely by using a voltage sensing relay instead of a DC-DC converter. For those using solar, find a solar regulator with dedicated load terminals and run your loads from these terminals. The solar regulator is configured to differentiate the current between the load and the charge terminals so that it will elevate the voltage only when the battery is sinking significant current and not when the loads are running. If you don't do this the regulator cannot distinguish between the load and charging the battery and will elevate the voltage whenever the loads are drawing current.

Large short term loads should not be connected to the load terminals of the solar regulator. Instead they should be connected direct to the battery, as the large load will pull the voltage down anyway and you do not want to overload the load terminals on the solar regulator. So for example your inverter or air compressor should be connected directly to the battery.

Minimising Depth of Discharge

If you don't have any way of charging your batteries whilst out on camp, or you only have a small solar panel, or if you know you are camping in dense forest, or if you know it will be very overcast, or if you don't have a DC-DC charger and you aren't driving long enough for the alternator to fully charge your battery, then there's a few things you can do to help keep your beer cold and minimise the depth of discharge of your aux battery.

- Connect your vehicle to a mains battery charger the day before you leave and keep it charging until you depart. Preferably use an intelligent charger. This ensures your batteries will be fully charged before leaving for camp.

- Turn your fridge on the day before you leave. This ensures your fridge and its contents are cold before leaving for camp.

- Do not put warm stuff in the fridge when you leave for camp. Put it in the fridge the day before or put it in your house fridge and transfer to the car fridge when you leave.

- Set the fridge to a very cold temperature whilst charging on mains and whilst driving. This accumulates the coldness which saves energy when running off batteries. A setpoint of -2 degrees is good. Put beer closest to the cooling elements, since the beer won't freeze at -2 degrees.

- Fill up your fridge as much as you can. This maximises the coldness that can be accumulated which saves energy when running off batteries. If you have spare space fill it with bottles of water, preferably frozen.

- Freeze stuff in your house fridge and put it in the car fridge just before departing. This might be meat or bottles of water or bait. The frozen stuff keeps the fridge cold and reduces the load on the fridge.

- When you arrive at camp, set your fridge to a higher temperature. Something like 7 degrees is ok. Beer still tastes pretty good at 7 degrees. Note anything above 4 degrees could lead to accelerated food spoilage and associated food wastage or poisoning.

- If you run your engine at any time during camp, set the fridge to a very cold temperature again, say -2 degrees. This ensures the fridge runs flat out whilst your engine is running. As soon as you shut down the engine set the fridge back to 7 degrees.

- Avoid opening the fridge. Wait until everyone is ready for the next round of beers, then swiftly retrieve the beers, keeping the fridge open for as little time as possible.

- Use a fridge cover to help insulate the fridge.

- Wrap your fridge in blankets or sleeping bags or any other insulating material but take care to not obstruct cooling fans or ventilation.

Inverters

Safety note: Inverters produce high voltages which can cause harm or death. Install according to instructions provided by the inverter manufacturer. Ensure the inverter cannot be exposed to moisture, dirt or dust. Connect loads directly to the inverter outlet to avoid the requirement of any permanent 240V distribution within the vehicle. If permanent 240V distribution is required this must be installed and checked by a certified electrician and must conform with relevant standards.

Inverters convert 12V DC to AC and allow you to run AC appliances from your 12V DC system. In Australia the AC voltage is 240V 50Hz. Electronics and step up transformers are used to change from direct current to alternating current and to increase the voltage.

Sizing your inverter

Your inverter needs to be sized to be able to supply steady state and peak loads. The electronics in your inverter have limited overload capability so it is important to check peak loads to ensure your inverter will be able to supply it. Most inverters are able to supply double their rating for short periods. To size your inverter for steady state conditions, add the wattage of the loads you will run simultaneously. To size it for peak loads, you need to find out what the peak loads are for the appliances you are powering. For example a rule of thumb for electrical motors is 5 x rated power during startup. TVs, fluorescent globes, etc all have startup inrush that needs to be taken into account.

As an example, let's assume we are running a 200W drill and a 60W incandescent light globe. The steady state calculation is 200 + 60 = 260W. For peak load, take the 200W rating of the drill and multiply by the inrush factor typical for electric motors (5): 200 x 5 = 1000W. So you need an inverter that can supply 260W continuous and 1000W peak. This would usually mean an inverter with a 500W continuous rating. It has to be oversized to be able to start the drill.

Modified Sine Wave vs True Sine Wave

AC appliances are designed to work with AC voltage supplies that are smooth and follow a sine wave profile. This sine wave profile is inherent in traditional power generation techniques (rotating generators) but not when generating power with electronics as is the case for inverters. Inverters can be either modified sine wave or true sine wave. Modified sine wave has a square wave voltage profile. True sine wave inverters use pulse width modulation to offer a smoother output closer in profile to a sine wave. The square wave of modified sine wave inverters does not matter much for inductive loads like motors or resistive loads like heating elements. However capacitive loads, such as the front end of most power supplies (laptop chargers, phone chargers, battery chargers, etc) can be worn out by square wave voltage inputs. The square wave causes current spikes at each edge of the wave. This can lead to premature failure of capacitive appliances. The increased failure rate is hard to quantify. Smaller inverters are inherently less able to provide much of a current spike due to their higher internal resistance, so small inverters offer less risk. For example I use a 120W modified sine wave inverter to charge our laptops without any issues after many years of use. The larger the inverter, the greater its capacity to source high current spikes, and the greater the case it is to go for a true sine wave inverter. I chose a true sine wave inverter for my 2500W inverter.

Supplying High Power AC Loads with Inverters

The current on a 12V system is a limitation for using inverters to supply high power loads. Volt drop and cable sizing becomes an issue. It becomes difficult to manage volt drop and cable sizes become impractical as power becomes large.

A typical 12V system might be good for say 100A on the 12V side. This means a maximum AC power of just 100 x 12 / 1.1 = 1090W (divide by 1.1 to account for inverter efficiency). So regardless of the size of your inverter, a typical 12V system might max out at around 1100W. Slightly higher peak power could be attainable. I use my system regularly to supply an appliance that uses around 1000W. I reckon it would be good for a bit more.

A well designed 12V system that could be reasonably fit in a car or camper trailer, with large batteries, large terminals, large diameter cables, soldered connections and short cable runs, may be good for around 200A. Rounding up, let's say it will be maxing out at around 2400W, which is the maximum rating of household appliances running off standard power outlets in Australia.

So you could potentially run a 2400W kettle or toaster off a well designed 12V system. They are resistive loads so do not have any inrush current. You'd be depleting your batteries pretty quick though. What about if you wanted to run a 2400W motor? Say a compressor? It's becoming impractical. The inrush is around 2400 x 5 = 12000W. This translates to around 1100A on the DC side after taking into account inverter efficiency. Cable sizes would be too large to terminate onto typical terminals found on batteries and inverters. At such a high current you'd need a bank of batteries to combat volt drop purely from the internal resistance of the batteries, regardless of the size of the cables you use. Even if you had two batteries that together could supply 1100A according to their datasheet, it would come at a significantly reduced voltage – maybe down to around 8V, which is below the threshold that most inverters could tolerate, so you'd need more batteries to combat startup volt drop. Mind you I have never tried to build a system that could start at 2400W motor, so I am speculating. If you've done it successfully let me know!

It depends on the nature of the load. If the load requires low torque at startup then the inverter will probably restrict its output and slowly accelerate the motor. But if you need high torque on startup then I reckon you'll struggle starting a 2400W motor with a 12V system.

Lithium Batteries

I have not used lithium batteries in dual battery setups myself. I have helped troubleshoot a couple of lithium systems on my travels. Some things to note about lithium compared to lead acid:

- Lithium can be discharged deeper and cycled more times. This means you can get away with a smaller battery and it should last longer.

- Lithium is much lighter than lead acid batteries.

- Lithium loses much less capacity at high discharge currents compared to lead acid.

- Lithium usually requires higher charge voltage and accurate detection of full charge. This means you rely on a specialized and expensive lithium DC-DC charger and if it fails whilst out bush and you try to directly charge from the alternator then the lithium battery will not charge properly.

- Lithium batteries will not absorb overcharge, not even a trickle charge. Overcharge will cause rapid wear and possible catastrophic failure. This could be especially risky if charging direct from the alternator, for example if the electronic charger fails whilst on the road.

- Lithium DC-DC chargers may trigger elevated charging voltages when loads like fridges start up (see section above "Overcharge from DC-DC Converters and Solar Regulators"). This means, even with sophisticated DC-DC chargers, a lithium battery may suffer from overcharge and a significant reduction in service life.

- Lithium batteries are very expensive.

- Lithium may not be as tolerant to mechanical disturbances and may be more likely to have internal failures, especially if going off road.

- When they fail, lithium batteries often catch fire, as reported on commercial aircraft and Tesla cars and more recently Hyundai electric cars. Lithium batteries used in dual battery systems (usually LiFePO4) are less susceptible to fires than some other lithium chemistries, but still have not proven themselves long term.

- Lithium batteries are not very tolerant to high temperatures, and wear out quickly when they get hot. This is why electric cars have sophisticated battery cooling systems with radiators / heat exchangers. A second battery in your car does not get such luxuries and may fail prematurely due to heat.

- Capacities of lithium batteries are often over-stated by their dodgy chinese vendors, eroding some of the benefits of lithium. Advertised capacities vary wildy for similar cells. Lead acid technology is much more established, and a lead battery of a certain form factor always has a capacity close to other batteries of similar size and weight.

- There can be an emotional bias towards lithium since it is the newer and more fancy technology and therefore attracts more status in the vehicle modding community. This may lead to advantages of lithium being over-stated.

- For an average Joe who just wants cold beer, going lithium could accidentally trigger a sequence of events that lead to a very fashionable and expensive state-of-the-art dual battery system costing many thousands of dollars. I feel bad when people get lead to believe they need to spend many thousands of dollars to keep their beer cold. Some people are spending out of control amounts of cash on their dual battery systems. They'll be stuck at work paying for that system rather than be out exploring the outback and drinking cold beer.

This is not a comprehensive analysis of lithium vs lead acid but for me I prefer lead acid. Lead acid is too cheap, reliable, easy to recharge, resistant to vibration, tolerant to overcharge, resistant to high temperatures, easy to fix and easy to find replacements. If lithium batteries are catching fire on planes I'm a bit concerned about what they'd do over a few billion corrugations.

If you combine the effects of high temperatures, lack of cooling systems, possible overcharge and vibration, the actual life of a lithium battery might be far less than the theoretical life, which erodes a lot of the long term value that lithium supporters claim.

If a battery failure were to occur I'd feel pretty bad about blowing away over 3 times the money of an equivalent lead acid battery. There is extra risk in putting so much money into a single supposedly longer lasting device, compared to having money in the kitty for when failures occur. However lithium does have advantages and is a worthy solution that should be considered in a design, particularly for its weight and depth of discharge advantages.

How does long term ownership costs compare? If you calculate the ownership costs based purely on battery price and maximum theoretical lithium life span then lithium may or may not end up slightly cheaper than lead acid depending on how expensive the lithium battery is and the assumed cycle life and capacity. There are some cheaper lithium battery options now available (at slightly more than double the price of lead acid) but I doubt they provide the same capacity and number of cycles as the brand name lithium batteries that cost 5 times more. The winner depends so much on the assumptions and prices chosen when calculating the total cost. But if you go spend 8 grand on the most fancy lithium setup in the world with super extreme plus battery management system and touch screen interface with automatic wifi firmware updates and remote bluetooth control with full snapchat integration and a huge LCD monitor dedicated to displaying how much status you acquire in the 4WD modding community then there's no doubt, in terms of long term ownership costs, you'd be much better off with a simple lead acid system.

Cable Sizing: Current Ratings and Volt Drop

Cables are sized according to volt drop and current capacity. Cables have a current carrying limit which cannot be exceeded. Current travelling through a conductor will cause volt drop across the length of the conductor, which needs to be kept within limits.

Cable current ratings are defined in manufacturer's datasheets. Values are dependent on heat dissipation and insulation tolerance to elevated temperatures. Calculate the current that will go through a cable based on what it is feeding. For example if it's feeding a 1000W inverter, then the current through the cable would be 1000 / 12 x 1.1 = 92A where multiplying by 1.1 is to take into account inverter efficiency. If the cable is to join your starter battery with your auxiliary battery, then you want to assume a large current so that you auxiliary battery will charge quickly and be able to contribute to starting your vehicle if the starter battery is depleted. At least 100A is a good figure for sizing this cable.

Volt drop is calculated by current x resistivity x length. Resistivity is usually given in Ohms / km so make sure your distance is also in km. Resistivity is resistance per unit length, and is governed by the cross sectional area of conductor and type of conductor. The actual values are provided in manufacturer's datasheets. Ensure you include the negative return cable in your calculation. It means you need to double the distance of the cable run.

As an example, let's say you have a 3m cable run from battery to the 1000W inverter mentioned above. The cable needs to be rated to 92A. Looking at datasheets for a particular manufacturer, this yields a minimum cable size of 25mm2 which has a resistivity of 0.734 Ohms / km. The total distance, including return cable run, is 0.006km. So the volt drop would be:

Volt Drop = 92 x 0.734 x 0.006 = 0.4V

Volt drop needs to be kept within the limits of the equipment being fed. For example many inverters can tolerate down to around 10.5V. The smaller the volt drop, the more efficient your system is. A typical figure in electrical design is 5%, which in a 12V system is 0.6V. So the arrangement above passes the test. A more stringent criteria for a 12V system would be say 0.2V. In this case the cable fails and it needs to be oversized to pass the volt drop criteria. The smallest cable size to provide less than 0.2V volt drop at 92A is 70mm2, which has a resistivity of around 0.27 ohms / km. The volt drop would be:

Volt Drop = 92 x 0.27 x 0.006 = 0.15V

For your heavy power cable runs, for example connecting the main battery to the auxiliary battery, and to a large inverter, it's important to size the cable correctly to avoid overheating it and avoid volt drop issues. Too much volt drop will mean your auxiliary battery takes too long to charge or your inverter cuts out. An easy option is to use the largest cable that is still practical to work with and terminate. This is around 70 to 95mm2 for typical battery and inverter terminals. Larger cables become difficult to work with but it depends on the installation.

Below is a table listing various cable sizes, typical current ratings (derated for being in contact with other surfaces according to Australian Standards), typical resistivity, and a volt drop calculation to provide a guide for cable sizing. Everything in the table is straight from the manufacturer, apart from the maximum current at 3m distance which is calculated bycurrent = volt drop / (resistivity x length). The table refers to PVC/PVC copper cables. When purchasing cables, make sure you specify mm2 of copper so that it is not confused with overall cable diameter.

| Cable Size | AWG | Resistivity | Current Rating | Overall Diameter | Max current for 3m cable length and 0.2V volt drop |

| mm2 | Equivalent | Ohms/km | Amps | mm | Amps |

| 1 | 17 | 18.2 | 13 | 2.8 | 1.8 |

| 1.5 | 16 | 12.2 | 16 | 3.1 | 2.7 |

| 2.5 | 14 | 7.56 | 23 | 3.6 | 4.4 |

| 4 | 12 | 4.7 | 31 | 4.5 | 7.1 |

| 6 | 10 | 3.11 | 40 | 5.1 | 10.7 |

| 10 | 8 | 1.84 | 54 | 6.0 | 18.1 |

| 16 | 6 | 1.16 | 72 | 6.9 | 28.7 |

| 25 | 4 | 0.734 | 97 | 8.4 | 45.4 |

| 35 | 3 | 0.529 | 119 | 9.4 | 63.0 |

| 50 | 2 | 0.391 | 146 | 10.9 | 85.3 |

| 70 | 2/0 | 0.27 | 185 | 12.4 | 123.5 |

| 95 | 3/0 | 0.195 | 230 | 15.2 | 170.9 |

| 120 | 4/0 | 0.154 | 267 | 17.3 | 216.5 |

| 150 | 300MCM | 0.126 | 308 | 18.8 | 264.6 |

| 185 | 350MCM | 0.100 | 358 | 21.1 | 333.3 |

| 240 | 500MCM | 0.0762 | 428 | 24.1 | 437.4 |

| 300 | 600MCM | 0.0607 | 495 | 26.9 | 549.1 |

| 400 | 750MCM | 0.0475 | 577 | 30.6 | 701.8 |

| 500 | 1000MCM | 0.0369 | 668 | 34.1 | 903.3 |

Terminations, Connections and Cable Routes

Terminals and connectors should be the right size for the cable. If the wrong size is used, the terminal can become a hot spot when under load and a potential point of failure. There is debate as to whether crimped connections should be soldered. Usually soldering provides a stronger connection less prone to becoming a hot spot, but some suggest soldered connections are brittle and will crack from vibrations. Bolted terminations must be tight and double checked before energizing the system.

It's handy to connect your solar panels, lights etc via plugs. It's extra work and doubles the amount of terminations, but it means you can easily remove them when you've finished your camping trip or if you have a problem with the equipment or its mounting system. Plugs should only be able to be made one way and should be held captive through some sort of latch. Anderson plugs are a popular solution. If you do a lot of offroading then expect some mounting and mechanical issues with your devices in which case being able to remove and refit them easily is important. Make a judgement as to whether it's worth the effort of using plugs on a case by case basis.

Cable lengths should be minimized to reduce volt drop and reduce the amount of cable potentially exposed to damage. Cable should be run within convoluted split conduit to protect them from mechanical damage. Avoid sharp bends, especially on larger cables. Avoid passing across sharp edges, such as those created when a hole is drilled. If passing cable through a drilled hole, first fit some split rubber seal around the hole or some other measure to cover the sharp edge. Rough roads and corrugations will otherwise cause the cable insulation to fail at the sharp edge.

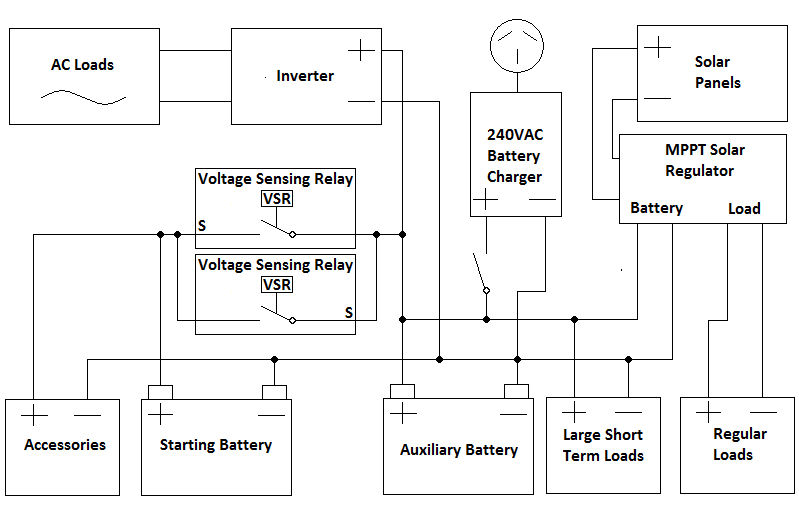

The Complete Installation

A complete system comprises of a dual battery system, solar panels, a solar regulator, an inverter and all the cables, connections, terminations and fuses / circuit breakers between. Add to that your auxiliary loads which are not covered here – fridges, lighting, extra cigarette lighter outlets, USB chargers, etc. In my opinion the best dual battery system is the dual voltage sensing relay with solar charging. It provides a good solution to charging the auxiliary battery from the alternator, sharing loads between the starting battery and the auxiliary battery, enabling the auxiliary battery to contribute to motor starting and enabling both batteries to be charged from a solar panel charging system. An advantage over the DC-DC converter is that it enables a higher charge rate, which means your auxiliary battery will be topped up quicker when your motor is running. It has a further advantage over the DC-DC converter that it does not keep the auxiliary battery at an elevated voltage all the time, which can cause unnecessary grid corrosion for no benefit. When you are cycling the battery, the solar panels are deployed and the solar regulator takes over, charging the battery to an elevated voltage with an optimized charging profile that reduces sulfation and charging the battery as fast as possible with an elevated voltage. It will also top up the starter battery with an elevated voltage, reducing sulfation on the starter battery. The batteries are cycled down every night so are not held at the elevated state of charge, which minimizes grid corrosion. This is exactly how the lead acid batteries are specified to operate according to their datasheets. A reduced float charge of 13.8V when not cycling, and an elevated charge of around 14.5V when cycling.

However each design has its compromises. I'd consider a DC-DC converter with a bypass switch, especially if I didn't have solar. The end user needs to decide what suits his or her application and budget.

The schematic for a complete system would look something like this, excluding fuses and circuit breakers:

A battery condition monitor is also useful. These can be as simple as a voltage display. Voltage is a good indicator of a battery's charge state if the battery is rested and not under load. More sophisticated condition monitors are available that calculate available battery capacity and other parameters.

Checkout outbackjoe on facebook

See also:

Manly Thermomix Review

Design Compromise

Emission Systems – Worth Tinkering?

Corrugations – Fast or Slow?

Why No Diesel Performance Chip?

After Market Add-ons and Other Touring / Camping Stuff

Our Electronic Gadgets for Touring / Camping

Camping / Touring / Travelling Phone and Internet Setup

Disconnect Negative Terminal when Welding

XXXX Gold – The Great Mystery of the Top End

back to 4WD, Touring and Camping

more articles by outbackjoe

Posted by: lawrenceloveduckedaeu.blogspot.com

Source: https://outbackjoe.com/macho-divertissement/macho-articles/design-guide-for-12v-systems-dual-batteries-solar-panels-and-inverters/

0 Komentar